RONALD ATKIN pays a personal tribute to the doyen of the tennis press box

The passing of Laurie Pignon at the age of 93 closes the book on the era of that larger-than-life group of sports writers – Peter Wilson, Geoffrey Green, Desmond Hackett and Laurie prime among them – who frequently appeared bigger than the events they were covering in the quarter century after World War II.

To have survived five years as a prisoner of war and a horrific winter march from Poland into Austria ahead of the advancing Russian army in 1945 persuaded Laurie to announce that he intended to enjoy every single day of the rest of his life, a promise he flamboyantly fulfilled.

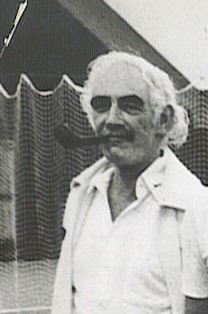

Pipe jutting and whisky tumbler in his fist, Laurie could carouse with the best but to his abilities to think big and fast and to write brilliantly could be added the minus factor of an hopelessness at spelling. Hence his preference for what he always called “an ab lib” delivered down the phone at top decibels.

Laurie was born in Horsham in August 1918 but always maintained his upbringing as a south Londoner. His first job after leaving Wilson’s School at Camberwell was in a sweet factory for three months until his father Fred, a sports writer with the Daily Mail, landed him work at Horse and Hound magazine. But being in charge of the hunt fixtures and the letters page was some way short of his idea of being a journalist.

He moved on to the Middlesex Chronicle for 25 shillings a week and did weekend moonlighting for the Women’s Sport agency, which sent him to his first Wimbledon in 1938. Having enrolled in the Surrey Yeomanry as a volunteer, Laurie was among the first to be called up on the outbreak of war in 1939 and in May 1940 was among the first to be captured as the British army fell back on Dunkirk. He narrowly escaped summary execution by an SS group, lined up with six others in front of a machine gun in a field and saved only by the arrival of another large group of British captives.

He spent much of the next five years as a forced labourer in the coal mines of Silesia, culminating in that forced winter march which ended in their German guards melting away as General Patton’s American army came over the horizon.

On demob, Laurie found work on the Daily Sketch as a sports sub-editor but was soon pressing for a writing job. He volunteered to cover the British hard court championships at Bournemouth as a holiday week but the sports editor, LV Manning (the father of J L Manning), paid him expenses instead. Manning senior then took Pignon with him to the 1946 Wimbledon and when the novice tennis writer came up with a great story from Court One about the favourite Jack Kramer suffering a blistered hand, Manning told him “That’s too good for you, I’ll have that”, crossed out the Pignon byline, wrote in his own and ordered Laurie to phone it over.

Soon enough, Laurie had his own column in the Sketch entitled “Opignon”, and when that paper merged with the Daily Mail in 1971, he became the Mail‘s tennis man, a post he held with distinction until required to retire aged 65 in 1983.

Pignon was never reluctant to charge towards purple prose in his eagerness to be ahead of the rest and he is responsible for one unforgettable gem from the French Open: “Miss Evert looked cool as a cucumber on a day when the ice creams were selling like hot cakes”.

Retirement came as a blow. “I didn’t want to go,” he told me once. “”I felt good, I was on top of my job. I never told the Mail but I was hurt when they made me retire.”

Perhaps that hurt spurred him into asking the editor David English, a frequent tennis partner, for a ride in Concorde to his final event, the US Open, in September 1983. The Mail obliged, but brought him back twice, first in 1989 for Chris Evert’s final Wimbledon and then again in 1991 when Bjorn Borg unwisely attempted a comeback at Monte Carlo. Borg’s wooden racket wasn’t the only thing out of date, Laurie discovered. “I went to the media room, got out my Olivetti portable, my flask of whisky and my pipe but all the others were staring into screens and drinking Coca-Cola.”

Laurie and his wife Melvyn Hickey, a former England women’s hockey captain, lived a full and happy retirement at their cottage at Sunbury by the River Thames, a place so compact that Melvyn compared it to a first-class railway compartment. But Pignon, thinking big as ever, referred to their spare bedroom as The East Wing and a paved courtyard containing two apple trees as The Lower Orchard.

Granted the rare (for a journalist) honour of membership of Wimbledon, Laurie played tennis and real tennis into his late 80s, cleverly arranging to play doubles with Melvyn. “I would shout ‘yours’ and she would run”. He attended every Wimbledon, striding around the media room proudly sporting his All England Club membership lapel badge, offering bonhomie, drinks and (if requested) advice. He was a great man and and I am by no means the only one who will miss him terribly.

- Click here to read Norman Giller’s own tribute to Laurie Pignon

- Post your memories and tributes to Laurie Pignon in the comments box below

My thanks – and those of everybody else who worked with Laurie Pignon at the Daily Mail – to Ron Atkin for such a splendid tribute. Laurie was more than just a very good tennis (or lawn tennis, as he preferred to call it) correspondent. He was a lively and loyal colleague, with almost unlimited energy and totally unlimited enthusiasm. When Laurie was in the office or at Wimbledon or in Scribes or wherever, his love of life inspired us all.