The Hillsborough disaster has been making headlines again this week. As we approach the tragedy’s 23rd anniversary, ANTON RIPPON reviews the autobiography of a newspaperman who found himself in charge of the newsroom that day

On the warm, sunny Saturday afternoon of April 15, 1989, Richard Harris was busy in his garden. The assistant editor of the Nottingham Evening Post had spent the morning overseeing that day’s Post. Now he was pulling up weeds and listening out for score flashes from Bristol City’s game against Blackpool.

There was no word of what was happening at Ashton Gate, however. BBC Radio was more concerned with events unfolding at Hillsborough, where Nottingham Forest and Liverpool were contesting a place in the FA Cup final.

When description of the play was replaced by reports of crowd trouble, Harris put down his trowel and listened more intently. An hour later, still in his grubby gardening clothes and with soil under his fingernails, he was back in his office at the newspaper’s headquarters in Forman Street, hastily gathering together the skeleton staff who would turn that night’s Football Post into one of the most important special editions that the paper had ever produced.

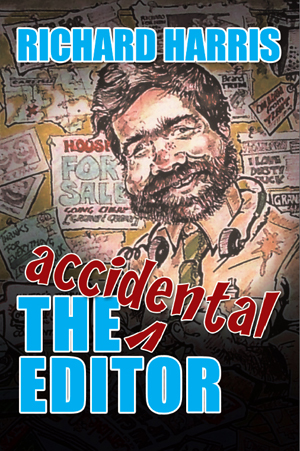

Twenty-three years later, it is a story that Harris relates in his autobiography The Accidental Editor. “In the middle of it all, I knew, were thousands of people from Nottingham – our readers … ”

For once, Harris really was the editor – Barrie Williams, Harris’s boss, was at the match as a spectator – and he set about turning the relatively humdrum sports edition into a newspaper covering what was turning out to be one of Britain’s biggest human tragedies.

For once, Harris really was the editor – Barrie Williams, Harris’s boss, was at the match as a spectator – and he set about turning the relatively humdrum sports edition into a newspaper covering what was turning out to be one of Britain’s biggest human tragedies.

The skeleton staff responded to the challenge magnificently, relishing the opportunity to “get involved in a real newspaper for a change”.

One of Harris’s biggest dilemmas was how to handle the increasingly graphic photographs that were now coming down the wire. “We had a duty to cover the horror of Hillsborough in all its dreadfulness, but equally we had a duty not to sicken our readers with photographs that were too harrowing and explicit. My solution was to use only pictures that showed people suffering but not near death.”

One photograph that Harris rejected in the heat of that day was of four teenaged girls clawing at the perimeter fence, their faces pinched and distorted by the wire mesh. In fact the girls survived, and the photograph became perhaps the iconic image of that day.

Harris writes: “Throughout the afternoon I was confident that Barrie – who I knew would be sitting in the grandstand, well away from the trouble – would phone as soon as he could (this was in the days before mobile phones) and issue brisk instructions on how we should be approaching the job. I like to think that the fact he didn’t showed that he was confident that the people running his newspaper in his absence would be up to the job.”

In fact, as Harris says in his book, it was the arrival of editor Williams that propelled him into a succession of increasingly high-profile jobs that eventually led to Harris himself becoming an editor, although, as he admits, it was not a successful move.

After 17 years on the Nottingham Evening Post, Harris became editor of the evening News & Star in Carlisle and of its sister weekly, the Cumberland News, but he was sacked in 1993, something that did not come as a surprise to him because he didn’t really think that he was cut out to be an editor, or was even a particularly good manager.

Then again, he never really wanted to become a journalist in the first place. As a naive 18-year-old, he joined the weekly Weston-super-Mare Mercury in his native Somerset only because it seemed slightly more agreeable than shovelling horse manure on a mushroom farm, a job that had been his introduction to working life.

“Because I’d never wanted to be a journalist until I was one is probably one of the reasons why being sacked didn’t hurt too much. I think my memoirs are a bit different to the norm because it all ends in the sort of failure that a lot of us prefer not to talk about.”

It was after a spell under editor Eric Price on the Western Daily Press in Bristol that Harris moved as a features sub to the Evening Post in Nottingham. If he thought Price was going to try to talk him out of leaving, he was disappointed.

“A few words of thanks from Eric would have been nice … but all I received in reply to my resignation letter was: ‘Dear Mr Harris, I am in receipt of your letter. As you say, you will leave on December 12. Yours sincerely, Eric Price.’”

So Harris made his way to Nottingham where the editor, Bill Snaith, an enormously polite 60-something with a highly polished head, offered him a job as a news reporter. Harris was surprised because the job for which he had applied was in the features department. Eventually, it was all sorted out.

It was at the Evening Post that I met Harris, when I too worked in the features department there in 1980. I recall an extremely nice young bloke with a mass of dark hair and a fine beard. He was welcoming to a newcomer, generous of thought and spirit, always wanting to start the day with a departmental coffee break in the canteen, which seemed very civilised.

Today, Harris, 62 (the beard is now snow white), happy and with grandchildren, works as a freelance journalist in Carlisle mainly covering Crown Court. He says: “I never wanted to be a journalist but I’ve loved every minute of it.” And I loved every page of his book.

- The Accidental Editor by Richard Harris (published by AuthorHouse UK Ltd, £12.99, is available from www.theaccidentaleditor.com)

- For more book reviews and news from the sports publishing business, click here

UPCOMING SJA EVENTS

Mon Apr 16: SJA Spring Golf Day, Surbiton GC. Click here for booking details.

Thu Apr 19: SJA Annual General Meeting, Fleet Street, 12.30pm. Click here for details.

Thu May 10: SJA Ladbrokes Lunch with former England cricket captain Alec Stewart. Booking details to be announced.

Mon Sep 24: SJA Autumn Golf Day, Muswell Hill GC. Booking details from Paul Trow at ptrow76780@aol.com