PETER WILSON on a definitive biography of one of the world’s greatest footballers

The reporting of European and world football has come a long way since Brian Glanville would drop the word catenaccio into his Sunday Times reports and World Soccer was the only outlet for information on how the game was played outside the British Isles, when “foreign” teams still retained an air of mystery.

Channel 4’s Football Italia and Gazzetta Football Italia, presented by James Richardson, raised the bar in the early 1990s by making the European game more accessible, ahead of satellite sports channels providing 24-hour worldwide coverage.

This opening of another world for the British football supporter, along with the influx of overseas players and managers to the domestic game, brought with it a need for newspapers and other publications to join TV in employing – usually on a freelance basis – their own specialists. Sid Lowe (The Guardian/Observer), Ian Hawkey (The Sunday Times/Telegraph) and Antony Kastrinakis (The Sun) are among those who have used their expertise to report on big European matches, stories and transfers.

Before them, two overseas sports journalists were the go-to men for anything relating to the game in Italy and Spain, making their initial impact on televised broadcasts of European football: the American-educated multi-lingual Italian, Gabriele Marcotti, and Guillem Balagué, the Barcelona-born alumni of Liverpool University, who writes song lyrics in his spare (yes, spare) time.

Before them, two overseas sports journalists were the go-to men for anything relating to the game in Italy and Spain, making their initial impact on televised broadcasts of European football: the American-educated multi-lingual Italian, Gabriele Marcotti, and Guillem Balagué, the Barcelona-born alumni of Liverpool University, who writes song lyrics in his spare (yes, spare) time.

As well as appearing on television, they have written for newspapers and published books on Paolo Di Canio (Marcotti), Lionel Messi (Balagué), Fabio Capello (Marcotti) and Pep Guardiola (Balagué), among others.

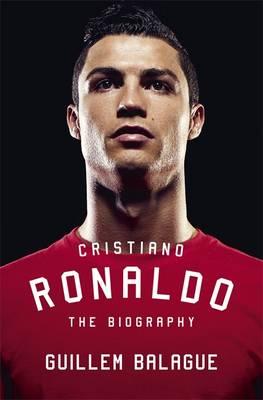

The latest of these fascinating subjects comes from Balagué. Cristiano Ronaldo – The Biography is first and foremost an excellent piece of journalism. Balagué goes deep into why Ronaldo is the player he is and the person he has become. With quotes from sports psychologists, a psychoanalyst, a professor of neurology and a couple of sociologists, do not expect anyone to be “over the moon” in this book.

The word “authorised” comes nowhere near this publication, as Balagué makes clear in a hugely entertaining prologue in which Ronaldo denies using “motherfucker” as his nickname for Messi, as Balagué reported in his previously published biography of the Argentine forward. He charts the controversy and the threat of an imminent lawsuit (which never materialised), and the strain it put on his relationship with the Real Madrid winger and, particularly, his powerful agent Jorge Mendes.

This, though, has not affected Balagué’s judgment of Ronaldo, for whom you can sense huge admiration, especially for the way he battled his way from a “dysfunctional” family life – his father was an alcoholic who died at 52 and his brother became a drug addict – to becoming the world’s best footballer with a fortune which Ronaldo himself boasted to the Daily Mirror in 2011 was then worth €250 million (with David and Victoria Beckham’s combined wealth estimated to be £240m in this year’s Sunday Times Rich List, CR7 has not done too bad).

Indeed, it is a shame his single-mindedness, which, okay, may have contributed to faults in his personality – if this book had an index then the words “crying or tears” would be on pages 71, 77, 128, 182 and 343 – is not replicated by some of England’s more promising stars: Ronaldo was climbing over fences at night to gain entrance to the gym to build up his strength at an age just younger than Jack Grealish was when he passed out on a street in Tenerife or Jack Wilshere was when standing outside a nightclub puffing on a cigarette. A footballer – anyone – who puts so much dedication into his or her career should be celebrated.

This book is meticulously researched and Balagué uses his Portuguese, Spanish and English contacts well. He has a unique style, frequently interrupting the narrative with “a brief digression here” or “more of that later”; it appears as if he is writing in real time – no more so than when he is trying to track down TV footage of Ronaldo’s father, Dinis, speaking about his son just a few months before his death.

Despite the regular absence of Dinis, men play a vital role in the Ronaldo story – even more so than his ever-present mother – from the coaches who spotted his potential early on, to the father figure that was, and still remains, Sir Alex Ferguson and those with which he has clashed, such as Jose Mourinho and Real Madrid president Florentino Pérez. Ronaldo will surely pass on the best of those relationships to his son, Cristiano Jr, although I pity the coach of any future schoolboy team that has him in their line-up. They might have to suffer a very pushy parent shouting instructions from the sidelines.

From taking his own ball to games with his childhood friends in Madeira – “the owner of the ball sets the rules”, warns Balagué – to wanting to run as fast as Thierry Henry or lift 90kg when pumping iron, Ronaldo has dedicated himself to reaching new goals, and it is this that puts doubts over his long-term future at Real Madrid. What is there left to achieve at the Bernabéu? He is the Liga side’s greatest goalscorer and has won every honour possible with the Spanish giants, although not as many as he would have hoped for when he signed from Manchester United for a world record £80 million in 2009.

Fitness permitting, Ronaldo could have five, even six, more years at the top. Paris St-Germain is his likely next stop and no doubt Balagué will be around to add further chapters in future reprints.

Until then, this is a gem of a book. File it under football, but maybe also sociology.

- Cristiano Ronaldo – The Biography by Guillem Balagué (Orion, £20)

VOTING IS NOW OPEN FOR SJA MEMBERS for the 2015 SJA British Sports Awards, sponsored by The National Lottery. For more information, and to cast your vote, click here

VOTING IS NOW OPEN FOR SJA MEMBERS for the 2015 SJA British Sports Awards, sponsored by The National Lottery. For more information, and to cast your vote, click here

- The SJA is the largest member organisation of sports media professionals in the world. Join us: Click here for more details

- This year, the SJA’s nominated good cause is The Journalists’ Charity. To find out more and how you can donate on a one-off or regular basis, go to www.journalistscharity.org.uk

UPCOMING SJA EVENTS

- Tue Dec 1: Young sports journalists’ networking drinks

- Thu Dec 17: SJA British Sports Awards, sponsored by The National Lottery

- Mon Dec 21: Journalists’ Charity Carol service, St Bride’s

2016

- Mon Feb 22: SJA British Sports Journalism Awards, sponsored by BT Sport