Steven Downes profiles an all-time British sporting great

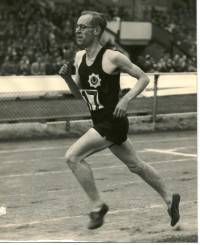

Appearances can be deceptive. Sydney Wooderson was the embodiment of that expression. As Harold Abrahams, the 1924 Chariots of Fire 100m Olympic gold medallist observed, “If someone were to point out Sydney Wooderson to you on the running track and tell you he was the athlete who had run a mile more quickly than any other human being, you just wouldn’t believe it.”

On week days, Wooderson looked like the epitome of the suburban commuter of the inter-war years, a short, slightly built solicitor’s clerk, hair Brylcremed back, short-sighted eyes peering out through thick, horn-rimmed glasses, “looking as if he had been mugged for his ration book”, as one biographer wrote.

Yet come the weekend, and stripped down to his Blackheath Harriers club vest and stepping on to a cinder running track, there was a transformation. Perhaps not quite of Superman proportions, for Wooderson’s skinny, white legs still stuck out incongruously from his baggy all-black kit. But once the race started, he was a ruthless competitor, dubbed “The Mighty Atom”, who managed to win European titles either side of the Second World War as well as setting world records for the mile, 800 metres and 880 yards, the latter with a time, 1min 49.2sec, that would remain unbeaten for 17 years.

The running career of Sydney Charles Wooderson, who has died in a Wareham nursing home, aged 92, will also be remembered as one that was denied by the circumstances of his time, as well as the frailties of his body.

Wooderson was denied his only chance of Olympic glory in 1936 through an ankle injury – he broke a bone in his foot while out walking with his brother, but kept the injury that might have ended his running career a secret from British Olympic team officials. Wooderson hobbled through his heat, unable to qualify for the final. “From the start all was not well with Wooderson,” the official British Olympic report recorded. “He was limping appreciably and was obviously at sixes and sevens.”

The 1,500m gold medal in those Berlin Games was won by the London-based New Zealander, Jack Lovelock, in 3min 37.8sec, a world record. Before the Games, and his injury, Wooderson had beaten Lovelock repeatedly after their first meeting, when Lovelock and Wooderson took gold and silver respectively at the 1934 Empire Games.

But by August 1937, his ankle healed after surgery, Wooderson was able to run the mile in 4min 6.4sec, faster than Lovelock and any other man had ever managed.

The record run came in a club meeting on August 28, at Motspur Park, just outside London. Wooderson had declined offers to go to America to race against Lovelock and the world record-holder, Glenn Cunningham, saying that he wanted to break the record in England.

Typically of the time, the venue chosen was a privately owned facility, run by a City bank, but the organisers, confident of Wooderson’s ability, arranged for four timekeepers from the AAA and set up the event as a handicap, to ensure that Wooderson had competition all the way through to the final lap. They also ensured that the track was re-measured, which was just as well, as it was found to be two inches (5cm) short of the required 440 yards. To allow for the short-coming, Wooderson’s start mark was set back a further 10 inches.

Wooderson was well-served by his pacemakers. Reg Thomas, himself once the British record-holder, went off with a 10-yard advantage, and kept that lead around the first lap, which Wooderson covered in 58.6sec. Wooderson got to within two yards of Thomas at the half-mile mark, where his time was 2:02.6, overtaking Thomas in the next half-lap. According to one eyewitness, the handicap arrangement was not entirely helpful to Wooderson: in the later stages, as he closed on tiring runners, the record-chaser found his way blocked.

“More than halfway through the race, hopelessly boxed in, Wooderson made a complete detour and entered the outside lane with nothing in front of him but space.”

With three-quarters of a mile covered in 3:07.2, Wooderson was within 50 yards of the leaders, his brother, Stanley (off a 140-yard start), and BC Eeles (65yds), but, according to another contemporary report, “it was on JV Powell, a former AAA half-mile champion, then 20 yards in front, that he kept his eyes.

“Powell overhauled the leaders about a furlong from home, and then Wooderson came along to finish first, about a yard and a half in front of Powell, who eased up nearing the tape. Wooderson’s time in a brilliantly run last quarter of a mile was 59.4sec”.

That Wooderson was capable of finishing with a sub-60sec last quarter is a significant indicator that he might even have been capable of quicker. Cunningham’s record, set at Princeton three years earlier, was beaten by 0.4sec, Wooderson’s own British best, set just a year earlier on a grass track, was shattered by more than 4sec.

Wooderson was carried from the track shoulder-high, his mother and father among the cheering fans along with his coach, Albert Hill, the 1920 Olympic 800 and 1,500m double gold medallist, and WG George, who in 1886 at Lillie Bridge, had been the last Englishman to break the mile world record.

Motspur Park, which continued to stage Surrey county championship meetings on its perfectly maintained cionder surface until the 1980s, was clearly a favourite venue for Wooderson, because he returned a year later to run in another club handicap event. This time, he claimed the 800m and 880yds world records.

But there were other occasions when fate would deny Wooderson. He had missed the 1938 Empire Games in Sydney, Australia, because he could not afford the time off work, where he had to sit his law exams. War broke out when Wooderson was just 25, and so might have been considered close to his peak as a middle distance runner. The 1940 and 1944 Olympics were cancelled.

And even in 1948, when the Olympics came to his home city, Wooderson, by then retired from the track but still a sporting hero with the British public, was denied the honour of carrying the flame into Wembley Stadium. The organisers preferred that a more statuesque figure should be seen on the post-war morale-building newsreels to carry out the symbolic task. Bill Collins, who organised the torch relay in 1948, said “such was the then organising committee’s obsession with a handsome final runner to light the Olympic flame that even the then Queen remarked to me ‘Of course we couldn’t have had poor little Sydney’.â€

Four years later, when the Games were staged in Helsinki, the Finns did the right thing, unconcerned that their  great track hero, Paavo Nurmi, was now balding and in pot-bellied middle aged: he lit the Olympic flame.

great track hero, Paavo Nurmi, was now balding and in pot-bellied middle aged: he lit the Olympic flame.

Yet in other respects, Wooderson carried the flame for British middle distance running, from the great WG George of the Victorian era through to Roger Bannister, who admits to being inspired to the first sub-four-minute mile by the sight of the battling Wooderson racing at the White City on the August Bank holiday in 1945.

Then, 54,000 sports-starved Londoners broke down the gates to get into the old stadium that had hosted the 1908 Olympics to see Wooderson take on Arne Andersson over a mile (the two men pictured together after the race). For Wooderson, it was barely six months after a bout of rheumatic fever and being told by doctors he could never run again, and – declared unfit for active service because of his poor eyesight – after a war spent digging latrines in the Pioneer Corps and repairing radios for the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

Meanwhile in Sweden, neutral and without wartime rationing, Andersson and his compatriot, Gunder Haegg, had been able to revise Wooderson’s world best marks for the mile three times apiece.

At White City, physically dwarfed by the Swede, Wooderson ought never to have stood a chance, yet he produced a battling performance and was only narrowly beaten in the final yards. Shortly afterwards they met again in Gothenburg. Again Andersson won by three yards, but Wooderson, at 31, recorded 4:04.2, his fastest ever, the fourth fastest of all-time.

Among the White City crowd for the first race had been the 16-year-old Bannister. “As boys we all have our sport’s heroes,” he said. “Wooderson from that day became mine. His run inspired me.

“He was always a gallant fighter, and I admired him as much for his attitude to running as for the feats he achieved. He was a methodical and unassuming athlete who gave up his time and energy to encourage youngsters even if they showed no promise. He believed that running was a worthwhile sport in itself, even if one could not achieve any great success.”

A year later, at the European championships in Oslo, Wooderson opted not to defend the 1,500m title he had won in Pais in 1938, but instead stepped up in distance to 5,000m, and with a characteristic finishing burst of acceleration (“in running style, he is as far removed from the classical as Salvador Dalà is from Rembrandt”, one contemporary reporter observed), he defied his lack of experience at the distance and duly won in the second fastest time ever. A certain Emil Zatopek was left trailing in fifth place.

By 1948, Wooderson was still capable of seeing off England’s best distance runners when that March he won the National Cross-country title over nine gruelling miles. Of British athletes of the modern era, only Steve Ovett, with an Olympic 800m title, Commonwealth Games 5,000m gold medal and the winner of the Inter-Counties Cross-country, has ever shown similar versatility over such a range of distances.

Throughout, Wooderson was modest, shy and unassuming. His retirement bungalow in Dorset had no memorabilia of his racing days on display. The only clue to his life as an athlete was his daily four-mile country walks, which he continued into his 80s, as long as his failing eyesight allowed.

“Poor little Sydney” finally received a royal honour when appointed MBE in 2000.

But he dismissed suggestions that he might have beaten Lovelock to the Olympic gold (“The ordeal of the big occasion would have affected me,” Wooderson always maintained. “I lacked Lovelock’s experience of international competition”) or Bannister to the four-minute mile.

“I do not think I would have done it,” Wooderson said. “It was a great strain keeping at the top. It was only because I lost six years that I started again. I felt I had to go out at the top and that spurred me to get back.

“The race against Andersson was my best race because I had not competed for so many years and yet I ran a time faster than my world record.”

Sydney Wooderson, MBE. Born Camberwell, south London, August 30, 1914. Died Wareham, Dorset, December 21, 2006. He is survived by his wife, Pamela, a son and daughter.

Read Andrew Baker’s Telegraph tribute to those sporting figures who died in 2006 by clicking here.