Four decades ago marked the start of a cricketing revolution, the effects of which shook the game. PHILIP BARKER reports.

Forty years ago this week, the touring Australian cricket team were supposed to be playing Sussex at Hove. Only 34 overs were bowled because of rain. Nothing remarkable about that.

But in the course of those three sodden days, Sussex and England captain Tony Greig had invited the team to his home for a party in a marquee. That evening, he issued a statement which set the wires humming.

“There is a massive cricket project involving most of the world’s top players due to commence in Australia this winter. I am part of it along with a number of England players,” he said.

Journalists Peter McFarline and Alan Shiell wrote the story which appeared in the Australian press. In the Daily Mail, Ian Wooldridge described it as a “brilliant ruthless coup. Overnight the whole balance of World Cricket has shifted.” John Arlott prepared his Guardian readers for “the most bitter battle in cricket history.”

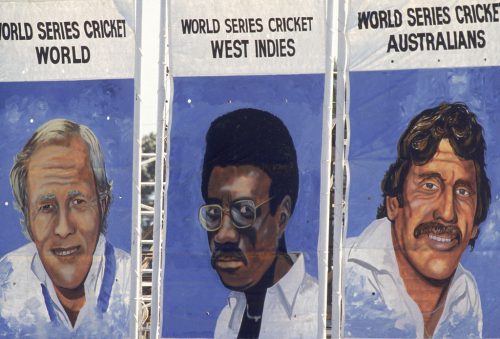

Detractors dubbed it a Pirate Circus. More formally, it was known as World Series Cricket (WSC). It has fascinated journalists ever since.

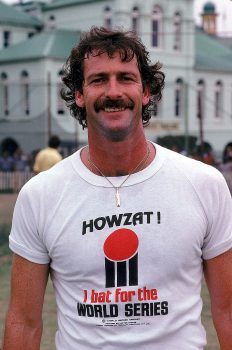

Only this week, the BBC’s Pat Murphy fronted a fascinating retrospective on Radio 5 live. In previous years, Sky Sports presenter Charles Colvile and the Australian writer Gideon Haigh have also related the story. In 2012 came Howzat! Kerry Packer’s War, a mini-series docudrama made by Channel Nine and shown on the BBC.

The Packer in question was an Australian television tycoon. To give him his full name Kerry Francis Bullmore Packer. He wanted the television rights for Test cricket for his Channel Nine network but was persistently snubbed by the Australian Cricket Board.

The Australian test team at the time were box office. Huge crowds came to watch, especially when fast bowlers Dennis Lillee, complete with bandido moustache, and Jeff Thomson were destroying England’s batting.

Lillee’s agent was television executive John Cornell who also knew Packer. The idea for WSC grew from their discussions. “Cricket is the easiest sport to take over. Nobody bothered to pay the players what they were worth,” said Packer.

He flew to England and even took part in the traditional match between the English and Australian press corps. His negotiations with officialdom at Lord’s proved less cordial.

The International Cricket Conference (ICC) decided that “the whole structure of cricket could be severely damaged by the type of promotion proposed by Mr Packer and his associates.”

They designated matches arranged by Packer’s organisation JP Sports (Pty) Ltd. as “disapproved” and decreed that “no player who after October 1st 1977 has played or made himself available to play in a match previously disapproved by the ICC shall thereafter be eligible to play in any Test match.”

Packer was furious and took them to court. At the High Court, Lord Justice Slade found in his favour. The verdict took five hours to deliver. Even so, most Packer signatories took no part in official cricket.

An exception was Warwickshire and England batsman Dennis Amiss, who continued playing county cricket.

“It was a very difficult time, I found the easiest thing was to be out on the field and trying to score runs, rather than coming back into the dressing room and being in a difficult situation,” Amiss told me years later.

WSC cricket featured a triangular format: Australians v West Indians v Rest of the World. But it says a lot for how the game has changed that no Indians were recruited for any of their teams.

In time there would be a white ball with black sightscreens, and coloured clothing. Critics described the new gear as “Pyjamas”

Originally banned from using the existing test venues, Packer’s groundsman John Maley developed ‘drop in pitches’ grown off-site in special trays and lowered into place at venues such as VFL Park, an Aussie Rules stadium.

The great Richie Benaud introduced WSC television coverage as “an exciting new concept”. The moment which defined it came in December 1977 when they switched on the lights “The day that floodlit cricket came to Melbourne was the day I knew World Series Cricket had arrived,” said Greig.

In time there would be a white ball with black sightscreens, and coloured clothing. Critics described the new gear as “pyjamas”.

The players also wore protective helmets. Prototypes would have looked more at home on a motorbike and initially players were not keen. But each WSC side had a battery of fast bowlers who were not shy about pitching it short. Australian skipper Ian Chappell described it as “the toughest season I’ve ever played in.”

Soon the new headgear gained acceptance and eventually everyone except Viv Richards wore one.

T20 wasn’t around in 1977, but extravaganzas such as the Indian Premier League and Big Bash in Australia have clearly learnt from WSC.

Back in the un-PC seventies, girls wearing tee-shirts and hot pants brought drinks onto the field. The WSC Australians came out to “C’mon Aussie C’mon”, written by Allan Johnston and Alan Morris from the Mojo advertising agency in Sydney. When the single was released it ousted Rod Stewart from the top of the Australian charts.

TV coverage was masterminded by Channel Nine Vice President David Hill and his director Brian C Morelli. Action was shown behind the bowler’s arm from both ends. Strange though it may seem, this was revolutionary. Eight cameras were used in all, and microphones were placed at the base of the stumps.

“Kerry Packer wanted to see televised cricket translating the excitement and tension onto viewers’ screens,” said Hill.

WSC placed the emphasis on one day cricket. When West Indies toured Australia in 1976, before Packer, they played only a single one day international. In 1979, the first season of official cricket after WSC, there were no fewer than 14, many under lights.

“We have to compete, we have to make it as attractive as we can and part of that is floodlit cricket and the razzamatazz,” said Amiss, later chief executive of Warwickshire, his home county club.

WSC cricket lasted only for two bitter years in which rival series went head to head in Australia. In 1979, both sides were ready to talk again and Packer finally won what he had wanted all along. To this day, Channel Nine transmits Test cricket in Australia.

The jury is still out on just how much the revolution benefitted ordinary professional players. Geoffrey Boycott, for one, remains unconvinced. The top players have central contracts. Those signed by the mega-rich Indian Premier League franchises command eye-watering fees.

In 2017 England all-rounder Ben Stokes landed a deal worth £1.7 million. The sums offered by Kerry Packer back in the seventies seem miniscule by comparison.

- The SJA is the largest member organisation of sports media professionals in the world. Join us: Click here for more details