Press relations were not a high priority for the organising committee as they prepared for the Olympics the last time they were staged in London, PHILIP BARKER writes. No World Press Briefing in those days, when the 1948 Games organisers and politicians paid some attention to the views of the press

In July 1946, George Barton of the Minneapolis Tribune filed a story after an interview with the British sportswriter, Frank Butler, which made Whitehall take notice. “I cannot understand why officials insist on England staging the Olympics in 1948 when that country doesn’t desire the Games, according to Frank Butler,” Barton had written.

London was chosen to host the 1948 Olympics by a postal ballot. Minneapolis had wanted them and were now after the 1952 Games.

“Minneapolis is welcome to the Games in 1948 as far as England is concerned,” Butler said. “Our country will not be prepared to handle the Games two years from now in the way we would like. It will take much longer than that to rebuild London and make it presentable to visitors.”

When they saw this back in London, alarm bells rang in Whitehall, where the splendidly named Harold Freese-Pennefather sprung into action in the best traditions of the Civil Service. He fired off a memo to Colonel Dick Edwards, in another corridor of power.

“Our view was that someone should let Mr Butler know the result of his irresponsible remarks,” he wrote. Warming to his task Freese-Pennefather then revealed his Master Plan.

‘‘What is wanted is a department whose job it would be not only to deal with offending columnists but to anticipate their harmful activities by putting out publicity giving the true facts of our intentions about the Games.

‘’If we get our material published first, there is less likelihood of the public in foreign places being misled by the fantasies of irresponsible local pressmen.’’

For Butler was not a lone voice.

The Evening Standard had gone on the attack with an editorial, “Call Off The Games”. It dismissed the Olympic Torch as “an antiquarian sham”, prompting relay organiser Bill Collins to remark to a colleague, ‘‘These pressmen can be the very deuce.’’

A new press department was formed, including the pre-war cricket commentator, Howard Marshall, and civil servant Sir Geoffrey Whiskard suggested another member for the team. “You may be unaware that we have here an assistant secretary who has an intimate knowledge of the behind the scenes workings of Olympic Games on previous occasions,” Sir Geoffrey wrote.

The man in question? Harold Abrahams, 1924 Olympic 100 metres champion and inspiration in part at least for Chariots of Fire.

By the summer, Press Officer RF Church reported, ‘‘We went off to a very slow start, office accommodation was in a state of rearrangement and the fuel crisis seemed to be a stop on any progress.’’

Church concentrated on winning over the British press. He boasted of conducting more than 150 interviews. “We can claim that the home market has been captured.”

The organisers started to produce a modest information bulletin in black and white and translated into French and Spanish. There was no room any for pretentious PR waffle on the “significance” of the logo, the design of the medals or anything else.

It advised that, “Visitors resident in hotels or other catering establishments are not required to produce a ration book for a stay of less than 28 days.”

There was also a word about petrol rationing for visiting journalists. “An allowance sufficient for 600 miles of motoring for the first two weeks of their stay.” Further coupons were issued on application.

Newspaper proprietors stumped up nearly £10,000 towards setting up a press club at the Civic Hall in Wembley. This opened the day before the Opening Ceremony, included a restaurant and “the use of a special silence room for work”. Press stewards were drawn from servicemen and students . Boy scouts were recruited to act as results messengers.

In 1948, Germany and Japan were not permitted to send teams to the Games, but what to do about their journalists? “It was agreed that free press seats at the Olympic venues should be provided only for press representatives from competing countries, but that if applications from representatives of the German newspapers were received, they should be allowed to purchase seats at the usual prices.”

Paper rationing was eventually eased and World Sports, the official magazine of the British Olympic Association, resumed publication in December 1947. It encouraged contributions from overseas. Among the contributors was Marcel Hansenne, a journalist from L’Equipe, who was also an athlete.

“It is a double-edged sword being a runner and a sportswriter. The writer can write about the runner but the runner cannot run away from the writer”, he wrote before taking 800m bronze in London.

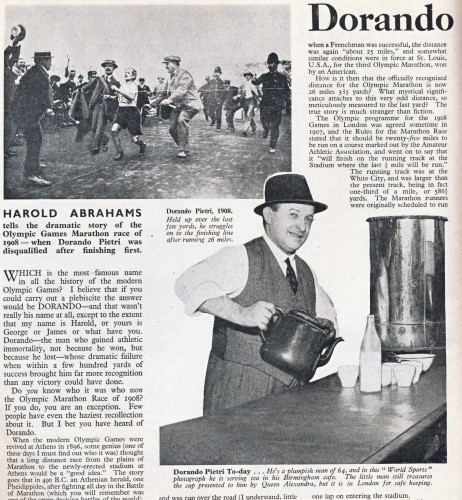

But for all the efforts of the press officers, there was one great Olympic hoax. A plumpish man of 64 serving tea in his Birmingham cafe claimed to be Dorando Pietri, the runner famously disqualified in the 1908 Olympic marathon after being helped across the line by officials.

Many ran with the story, including even the BOA-published World Sport (the accompanying article, pictured left, written by Abrahams, did not mention the Birmingham cafe, so the use of the picture may have been the work of the editorial desk). But the cafe owner was an impostor. The real Dorando had died six years earlier.

SJA WORKING LUNCH: Baroness Grey-Thompson on the 2012 London Paralympics. Thu Nov 17: click here for booking details

- Who will you vote for as Britain’s Sportsman, Sportswoman and Team of the Year? See Ian Cole’s overview of the leading candidates by clicking here.

- Follow news of the SJA British Sports Award on Twitter with the hashtag #SJA2011

- Mo Farah’s historic claim on your votes By Randall Northam

- Mark Cavendish keeps his promise in his race of his life By Richard Williams

- England’s Ashes-winning cricket team are top of the world. By Ian Cole

- Laura Davies gets back on song with Solheim. By Patrick Kidd

- Alastair Cook’s tour helped drag England from the brink. By Ian Cole

- Chrissie Wellington is an Iron Lady who deserves your vote. By Steven Downes

- Nick Matthew, squash’s heir to Barrington. By Rod Gilmour

- Sarah Stevenson gets a big kick from taekwondo. By Trevor Baxter

- Walker Cup amateurs did a professional job. By Paul Trow

- How Greene boy from the valleys overcame hurdles. By Gary Baker

- SJA members can cast their votes by clicking here.

- The awards will be presented at our gala annual lunch in London on December 7. Don’t miss out on being there – click here for a ticket booking form, with SJA members entitled to buy two tickets at half the usual price.